- National memorial to honor NC firefighter who died on duty during Hurricane Helene

- Gov. Josh Stein extends State of Emergency for western NC wildfires

- Gov. Stein extends state of emergency for NC wildfire threat

- Governor Stein extends state of emergency for NC wildfire threat

- Governor Stein extends emergency in 34 NC counties amid wildfire threat

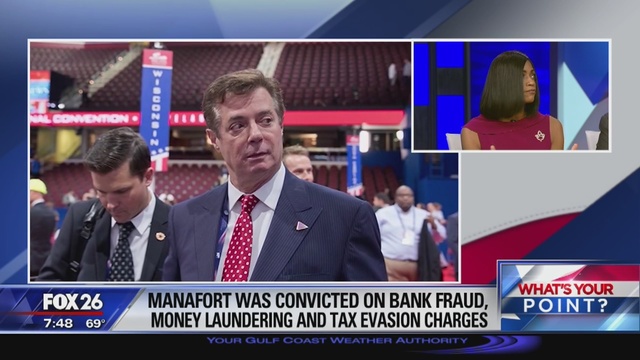

Manafort sentence considered light

HOUSTON (FOX 26) – This week’s panel: Jessica Colon – Republican strategist, Nyanza Davis Moore – Democratic Political Commentator Attorney, Bob Price – Associate Editor of Breitbart Texas, Antonio Diaz- writer, educator and radio host, Tomaro Bell – Super Neighborhood leader, Kathleen McKinley – conservative blogger, join Greg Groogan in a discussion about the 47 month sentence received by Paul Manafortm the former Trump campaign manager.

A judge’s decision to sentence President Donald Trump’s former campaign chairman to less than four years in prison – a fraction of the penalty called for in government guidelines – sparked widespread anger Friday and opened up a conversation about whether the justice system treats different crimes and criminals fairly.

Judge T.S. Ellis III’s comment that Paul Manafort had lived an “otherwise blameless life” was particularly galling to those who pointed out that Manafort’s past included work for people such as Philippine strongman Ferdinand Marcos and Congolese dictator Mobutu Sese Seko.

Sen. Cory Booker, a Democratic presidential candidate, told “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” Thursday night that the criminal justice system “treats you better if you’re rich and guilty than if you’re poor and innocent” and preys upon the most vulnerable such as “poor folks, mentally ill folks, addicted folks and overwhelmingly black and brown folks.”

Asked if he was shocked, Booker replied, “No, this criminal justice system can’t surprise me anymore.”

Manafort, 69, was convicted by a jury in Virginia of eight felony tax and bank fraud charges. Probation officials calculated a guideline range of 19.5 to 24.5 years.

Many observers raised the case of Crystal Mason, a black woman from Texas who was sentenced in state court last year to five years in prison for voting illegally in 2016, while she was on supervised release from a federal conviction. Mason said she didn’t know she wasn’t allowed to vote.

Her lawyer, Alison Grinter, said Friday that the judge’s comment about Manafort being “blameless” was infuriating, especially considering that he is awaiting sentencing on a different case in Washington, where he faces up to 10 more years. The Washington judge who will sentence him next week has the option to impose that sentence either concurrently or consecutively.

“I’m absolutely aghast. I hardly recognize the judicial system,” Grinter said. Mason and “so many other folks like her have come to expect this kind of disparity. It’s only now that we’re paying attention to it.”

Grinter pointed out that her client’s original crime was a single tax-related federal charge, and she received the maximum sentence. Manafort, on the other hand, received more than 15 years less than what was called for under the low end of the guideline range.

The most recent statistics from the U.S. Sentencing Commission show that, in fiscal year 2017, roughly half of all federal sentences came in below the guidelines, while only 3 percent went above the guidelines. Roughly three-fourths of all tax cases came in below the guidelines in that fiscal year, according to the commission.

In Manafort’s case, the judge called the guideline range “excessive.” During Thursday’s hearing, he noted that the guidelines were recently changed to calculate higher sentences in tax cases. As a result, many tax evaders who similarly avoided millions of dollars in taxes over the years received much lighter sentences, sometimes less than a year. Defense lawyers cited those cases, and Ellis said he arrived at his sentence in part to avoid unwarranted disparities.

Ellis , who was born in Bogota, Colombia, was appointed to the bench by President Ronald Reagan in 1987.

A review of several of Ellis’ cases by The Associated Press found that he is sometimes lenient, meting out lower-than-recommended sentences in multiple fraud and drug cases this year and last. In one drug case, he sentenced a defendant to just over four years, nearly five years less than the nine years called for by the lower end of the guideline range.

However, most of his sentencing departures could be measured in months.

In another high-profile case in 2009, Ellis sentenced Congressman William J. Jefferson to 13 years in prison for bribery and fraud, significantly less than the 27 to 33 years calculated for Jefferson under the sentencing guidelines. Still, it was the longest-ever prison sentence for a member of Congress. Ellis later released him after he had served less than half his sentence due to a Supreme Court ruling in another bribery case.

Jefferson, who is black, told the AP on Friday that he believed Manafort’s sentence was “grossly inequitable.”

“I just count it as another recognition of a fault in the system that seems to be ever-present when it comes to comparing how blacks and whites who are similarly situated are treated differently,” he said. The disparity “keeps showing its ugly face.”

Marc Mauer, executive director of The Sentencing Project, a group that works to reform sentencing policy and address racial disparities in the criminal justice system, said the system is a function of race and class disparities.

Manafort and other wealthy white-collar defendants are able to afford the best defense money can buy, he said. He questioned why the legal system does not “provide those same resources to the indigent defendants, who are the bulk of the people going through the court system?”

Another way to look at the issue, he said, is “that many people are getting harsh sentences. If there’s one thing that characterizes the American court system, it’s that our sentences are very severe by any international standards.”

Not everyone thought the sentence was too lenient. Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani said Manafort had been treated out of proportion to what he had done. Giuliani blamed prosecutors for what he called “excessive zeal.”

“He’s not a terrorist. He’s not an organized criminal,” said Giuliani, who was known for his tough-on-crime approach when he was mayor of New York City. “He’s a white-collar criminal.”

___

Associated Press writers Errin Haines Whack in Philadelphia, Matthew Barakat in Alexandria, Virginia, Jonathan Lemire in New York and AP researcher Jennifer Farrar in New York contributed to this report.

ALEXANDRIA, Va. (AP) – Former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort has been sentenced to nearly four years in prison for tax and bank fraud related to his work advising Ukrainian politicians, much less than what was called for under sentencing guidelines.

Manafort, sitting in a wheelchair as he deals with complications from gout, had no visible reaction as he heard the 47-month sentence. While that was the longest sentence to date to come from special counsel Robert Mueller’s probe, it could have been much worse for Manafort. Sentencing guidelines called for a 20-year term, effectively a lifetime sentence for the 69-year-old.

President Donald Trump said Friday that he feels “very badly” for Manafort.

“I think it’s been a very, very tough time for him,” Trump said before leaving Washington to survey tornado damage in Alabama.

Judge T.S. Ellis III, discussing character reference letters submitted by Manafort’s friends and family, said Manafort had lived an “otherwise blameless life.”

Manafort has been jailed since June, so he will receive credit for the nine months he has already served. He still faces the possibility of additional time from his sentencing in a separate case in the District of Columbia, where he pleaded guilty to charges related to illegal lobbying.

Manafort told the judge that “saying I feel humiliated and ashamed would be a gross understatement.” But he offered no explicit apology, something the judge noted before issuing his sentence Thursday.

Manafort steered Trump’s election efforts during crucial months of the 2016 campaign as Russia sought to meddle in the election through hacking of Democratic email accounts. He was among the first Trump associates charged in the Mueller investigation and has been a high-profile defendant.

But the charges against Manafort were unrelated to his work on the campaign or the focus of Mueller’s investigation: whether the Trump campaign coordinated with Russians.

A jury last year convicted Manafort on eight counts, concluding that he hid from the IRS millions of dollars he earned from his work in Ukraine.

Manafort’s lawyers argued that he had engaged in what amounted to a routine tax evasion case and cited numerous past sentences in which defendants had hidden millions of dollars from the IRS and served less than a year in prison.

Prosecutors said Manafort’s conduct was egregious, but Ellis ultimately agreed more with defense attorneys. “These guidelines are quite high,” Ellis said.

Neither prosecutors nor defense attorneys had requested a particular sentence length in their sentencing memoranda, but prosecutors had urged a “significant” sentence.

Outside court, Manafort’s lawyer Kevin Downing said his client accepted responsibility for his conduct “and there was absolutely no evidence that Mr. Manafort was involved in any collusion with the government of Russia.”

Trump said Downing went out of his way to say there was no collusion with Russia.

“The judge, I mean for whatever reason, I was very honored by it, also made the statement that this had nothing to do with collusion with Russia. … Guess what, there is none,” Trump said.

Ellis didn’t say there was no collusion. He said Manafort wasn’t being sentenced for collusion.

Ellis noted that when Manafort’s legal team argued before trial last year that the special counsel’s mandate to probe Russian collusion should have prevented the tax and bank fraud case against the former Trump campaign chairman, the judge dismissed their concerns. Ellis said he “concluded that it was legitimate” for Mueller’s office to charge Manafort with financial crimes even if the case was not about collusion.

Prosecutors left the courthouse without making any comment.

Though Manafort hasn’t faced charges related to collusion, he has been seen as one of the most pivotal figures in the Mueller investigation. Prosecutors, for instance, have scrutinized his relationship with Konstantin Kilimnik, a business associate U.S. authorities say is tied to Russian intelligence, and have described a furtive meeting the men had in August 2016 as cutting to the heart of the investigation.

After pleading guilty in the D.C. case, Manafort met with investigators for more than 50 hours as part of a requirement to cooperate with the probe. But prosecutors reiterated at Thursday’s hearing that they believe Manafort was evasive and untruthful in his testimony to a grand jury.

Manafort was wheeled into the courtroom about 3:45 p.m. in a green jumpsuit from the Alexandria jail, where he spent the last several months in solitary confinement. The jet black hair he bore in 2016 when serving as campaign chairman was gone, replaced by a shaggy gray. He spent much of the hearing hunched at the shoulders, bearing what appeared to be an air of resignation.

Defense lawyers had argued that Manafort would never have been charged if it were not for Mueller’s probe. At the outset of the trial, even Ellis agreed with that assessment, suggesting that Manafort was being prosecuted only to pressure him to “sing” against Trump. Prosecutors said the Manafort investigation preceded Mueller’s appointment.

The jury convicted Manafort on eight felonies related to tax and bank fraud charges for hiding foreign income from his work in Ukraine from the IRS and later inflating his income on bank loan applications. Prosecutors have said the work in Ukraine was on behalf of politicians who were closely aligned with Russia, though Manafort insisted his work helped those politicians distance themselves from Russia and align with the West.

In arguing for a significant sentence, prosecutor Greg Andres said Manafort still hasn’t accepted responsibility for his misconduct.

“His sentencing positions are replete with blaming others,” Andres said. He also said Manafort still has not provided a full account of his finances for purposes of restitution, a particularly egregious omission given that his crime involved hiding more than $55 million in overseas bank accounts to evade paying more than $6 million in federal income taxes.

The lack of certainty about Manafort’s finances complicated the judge’s efforts to impose restitution, but Ellis ultimately ordered that Manafort could be required to pay back up to $24 million.

In the D.C. case, Manafort faces up to five years in prison on each of two counts to which he pleaded guilty. The judge will have the option to impose any sentence there concurrent or consecutive to the sentence imposed by Ellis.

___

Associated Press writer Eric Tucker contributed to this report.