- Here’s how Austin-area leaders are preparing for wildfire threats this summer

- Harris County sues Trump administration, cites threat to hurricane season preparedness

- Prescribed burn in Morrow Mountain aims to prevent future wildfires

- Prescribed burns aim to prevent wildfires in Stanly County

- Prepare for hurricane season with the Town of Leland Hurricane Expo

CSU predicts above average activity for 2020 hurricane season

(CBS News) — As the world battles the coronavirus crisis, researchers are warning of a potentially active Atlantic Ocean hurricane season, which kicks off June 1 through the end of November.

For the 37th year in a row, Colorado State University (CSU) issued its hurricane season forecast Thursday — and the numbers appear significantly above normal.

Specifically, the team forecasts 16 named tropical systems; 12 is the average. Eight of those named systems are forecast to reach hurricane status, with winds greater than 74 mph; Six is the usual amount per year. CSU is also forecasting more major hurricanes than is typical per year: four as opposed to the average of 2.7.

The forecast is also alarming in that it’s calling for a nearly 70% chance a major hurricane — which is at least a Category 3 storm with sustained wind speeds of 111 to 129 mph — makes landfall somewhere along the U.S. coast. That’s 130% of the long-term average.

The Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) — a collective measure of overall activity in terms of number, intensity and longevity of storms — is forecast to be 140% of the long-term average.

Along with these forecasts, research also shows tropical systems are intensifying more rapidly and likely slowing down their forward motion due — at least partially — to a warmer globe. This is leading to more damage due to stronger winds, heavier rain and flooding.

When multiple crises compound, like COVID-19 and a landfalling hurricane, climate scientists call this a threat multiplier.

“There are only so many resources that we can marshal to mitigate these crises as they become increasingly more frequent and widespread,” Professor Michael Mann, director of the Earth System Science Center at Pennsylvania State University, told CBS News. “We’ll be forced into a very troubling triage environment where all we can hope for is to limit the damage, death and destruction.”

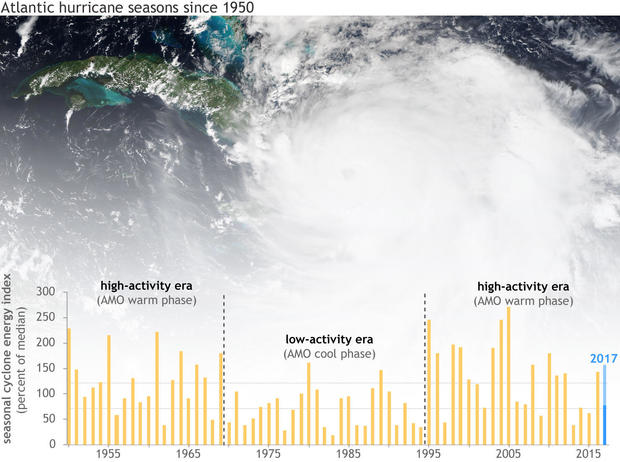

To construct the hurricane season forecast, the CSU team analyzes several parameters, weighed against past hurricane seasons, including sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic, the presence or lack thereof of El Niño in the tropical Pacific Ocean and the phase of a natural oscillation in the Atlantic Basin called the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation.

The most significant factor in determining how active a hurricane season may turn out to be is how warm the ocean is. Currently, sea surface temperatures are above normal across most of the tropical development regions in the Atlantic. This is especially true in the subtropical Atlantic close to the U.S. where the Gulf of Mexico, as a whole, is 5 degrees Fahrenheit above normal, with some pockets inflated by a striking 8 degrees.

Warmer sea surface temperatures provide more energy for developing systems. This does not always cause more storms to form, but that “higher-octane fuel” does power stronger systems.

That fact is significant because an increase in storm intensity does not just cause a modest increase in damage, the change can be exponential. For instance, a storm with winds of 150 mph can produce 250 times the damage compared to a storm with winds of 75 mph. So, if water temperatures remain far above normal for the season it is logical to assume, a landfalling storm will likely cause more damage.

Will El Niño play a role this year?

The CSU team also factors in the expected phase of El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) – a natural cycle found in the Equatorial Pacific waters. Even though the phenomenon is found thousands of miles away, there is a strong connection between ENSO and the degree of tropical activity in the Atlantic basin.

When ENSO is in its warm El Niño phase, that powers stronger jet stream winds into the Atlantic, disrupting tropical systems, tearing them apart. However, this summer and fall an El Niño is not forecast.

Rather this season, either neutral conditions should dominate or even a cool La Niña may develop. That translates to weaker atmospheric winds and a more nurturing Atlantic environment for tropical systems to flourish.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of this forecast is the likely presence of a negative Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), a naturally occurring cycle which swings from cool to warm phases every couple of decades. The negative phase corresponds to cooler than normal “North” Atlantic Ocean waters.

In periods where the AMO is in cool phase, Atlantic hurricane seasons tend to be less active, which is the opposite of what is expected this year.

This upcoming season, however, other factors like the absence of El Niño in the Pacific and toasty Atlantic Ocean temperatures may outweigh the overall climate cycle.

While warmer than normal Tropical Atlantic waters do not occur in every region, every year, they are becoming increasingly prominent.

Professor Mann said year-to-year variability is now bolstered by warmer ocean waters due to global heating. Some 90% of excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases is stored as energy in the oceans, yielding record setting ocean heat content, year after year.

“Bottom line,” Mann said, “Human-caused warming is leading to increasingly intense tropical cyclones in the Atlantic and other basins.”