- Seven months after Hurricane Helene, Chimney Rock rebuilds with resilience

- Wildfire in New Jersey Pine Barrens expected to grow before it’s contained, officials say

- Storm damage forces recovery efforts in Lancaster, Chester counties

- Evacuation orders lifted as fast-moving New Jersey wildfire burns

- Heartbreak for NC resident as wildfire reduces lifetime home to ashes

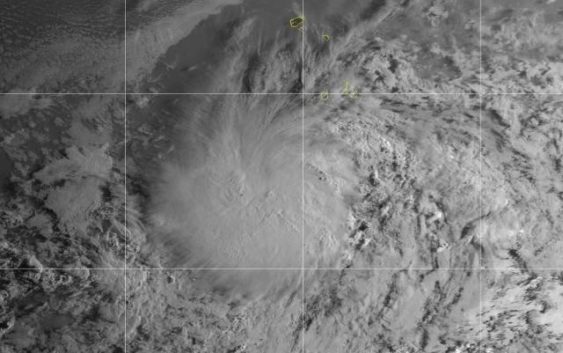

Tropical Storm Larry Forms in the Atlantic

Tropical Storm Larry formed in the eastern Atlantic Ocean early Wednesday, becoming the 12th named storm of the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season and the fourth in the past week as the season enters its busiest period.

The storm was about 275 miles south of the Cape Verde Islands, off the west coast of Africa, moving westward at about 22 mph with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph, the National Hurricane Center said in an update at 11 a.m. Eastern time. Larry was expected to strengthen and become a hurricane on Thursday, the hurricane center said.

There were no coastal watches or warnings in effect.

It has been a dizzying few weeks for meteorologists who have monitored several named storms that formed in quick succession in the Atlantic, bringing stormy weather, flooding and damaging winds to parts of the United States and the Caribbean.

In addition to Ida, which walloped Louisiana on Sunday as a Category 4 hurricane, there were also Julian and Kate, both of which quickly fizzled out within a day. Not long before them were Tropical Storm Fred, which made landfall in the Florida Panhandle in mid-August, Hurricane Grace, which hit Haiti and Mexico, and Tropical Storm Henri, which knocked out power and brought record rainfall to the Northeastern United States less than two weeks ago.

The quick succession of named storms might make it seem as if the Atlantic is spinning them up like a fast-paced conveyor belt, but their formation coincides with the peak of hurricane season.

The period between August and October is when 78% of tropical storms, 87% of minor hurricanes and 96% of major hurricanes occur, said Dennis Feltgen, a meteorologist and spokesman for the National Hurricane Center. Maximum activity takes place in early to mid-September, he said.

The links between hurricanes and climate change are becoming more apparent. A warming planet can expect stronger hurricanes over time, and a higher incidence of the most powerful storms — though the overall number of storms could drop, because factors like stronger wind shear could keep weaker storms from forming.

Hurricanes are also becoming wetter because of more water vapor in the warmer atmosphere; scientists have suggested storms like Hurricane Harvey in 2017 produced far more rain than they would have without the human effects on climate. Also, rising sea levels are contributing to higher storm surge — the most destructive element of tropical cyclones.

A major United Nations climate report released in August warned that nations have delayed curbing their fossil-fuel emissions for so long that they can no longer stop global warming from intensifying over the next 30 years, leading to more frequent life-threatening heat waves and severe droughts. Tropical cyclones have likely become more intense over the past 40 years, the report said, a shift that cannot be explained by natural variability alone.

Ana became the first named storm of the season on May 23, making this the seventh year in a row that a named storm developed in the Atlantic before the official start of the season on June 1.

In May, scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration forecast that there would be 13 to 20 named storms this year, six to 10 of which would be hurricanes, including three to five major hurricanes of Category 3 or higher in the Atlantic. In early August, in a midseason update to the forecast, they continued to warn that this year’s hurricane season will be an above average one, suggesting a busy end to the season.

Matthew Rosencrans, of NOAA, said that an updated forecast suggested that there would be 15 to 21 named storms, including seven to 10 hurricanes, by the end of the season on Nov. 30.

Last year, there were 30 named storms, including six major hurricanes, forcing meteorologists to exhaust the alphabet for the second time and move to using Greek letters.

It was the most named storms on record, surpassing the 28 from 2005, and the second-highest number of hurricanes. This article originally appeared in The New York Times.