- NC's FEMA aid extension for Hurricane Helene recovery denied

- NC's FEMA aid extension for Hurricane Helene recovery denied

- NC Gov. Stein pledges continued Hurricane Helene recovery support in 100-day address

- Austin adopts new map that greatly expands area at risk of wildfire

- CenterPoint Energy accelerates infrastructure improvements ahead of hurricane season

Texas is facing longer, drier droughts and more wildfires. Is San Antonio ready?

As of late last month, San Antonio is once again in drought — a familiar reality for those who live in South Texas. With continued dry weather in the forecast, officials expect to issue further water restrictions in the coming weeks.

Amid historically dry spring conditions, rashes of wildfires have scorched their way across the state, including the Das Goat Fire, which burned more than 1,000 acres before it was extinguished April 2 just west of San Antonio.

On Saturday afternoon, multiple fire crews battled a brush fire at Camp Bullis, according to the Leon Springs Fire Department. According to the National Weather Service, a red flag warning — meaning any fires that develop could spread rapidly — remained in effect until 8 p.m. that evening, and the weather service said “elevated to near critical fire conditions” were forecast Sunday, Wednesday and Thursday this week.

As weather conditions become more severe due to climate change, drier and longer droughts are likely to become more prevalent, said state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon. And more severe drought is likely to lead to more wildfires.

Texas will almost certainly face a new “drought of record” — the most severe drought recorded since record-keeping began — in the coming years. As of now, the record is a seven-year dry spell that gripped the state from roughly 1950 to 1957. Texas’ driest year on record, however, was 2011, the beginning of another multiyear drought.

“We have most of the state in drought right now,” Nielsen-Gammon told the San Antonio Report last week. “And there’s no indication of the drought letting up soon.”

Is San Antonio prepared?

Defining drought in San Antonio

The Edwards Aquifer is San Antonio’s main source of drinking water, accounting for 51.2% of the water the San Antonio Water System utilizes. The health of the aquifer defines the region’s drought rules.

The Edwards Aquifer Authority, which regulates the aquifer’s use, declares drought for this region when the Edwards’ monitoring well drops below an average of 660 feet above sea level for 10 or more days. In response, on March 10, city officials and SAWS announced Stage 1 watering restrictions, which include limited lawn-watering days and times. The more severe a drought, the more severe the restrictions issued by local water management entities like SAWS.

This summer is expected to be particularly dry, Nielsen-Gammon said, thanks to La Niña — a weather phenomenon that causes the polar jet stream to move north, causing southern states to see warmer and drier conditions than usual.

Forecasts from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration echo Nielsen-Gammon; as of late February, almost 60% of the country is in drought, the highest percentage since 2013.

SAWS is likely to issue Stage 2 restrictions in the next couple of weeks, said Roland Ruiz, general manager of the Edwards Aquifer Authority. San Antonio was last in Stage 2 in April of last year, but only for about a week. Like Stage 1, Stage 2 limits watering with an irrigation system or sprinkler to once a week, but it further restricts watering hours on the designated watering day.

SAWS has four stages of drought restrictions, although it has never declared Stage 3 or Stage 4 since it began keeping record in the early 2000s.

That’s because even in drought, the Edwards Aquifer is protected, Ruiz said.

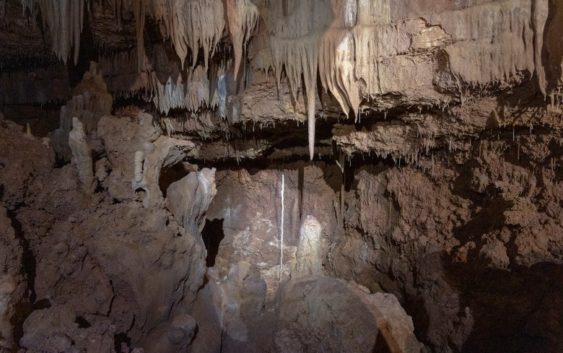

For one thing, it doesn’t face evaporation from the hot Texas sun. It also recharges very quickly, said EAA Senior Public Affairs Administrator Ann-Margaret Gonzalez. The Edwards is a karst aquifer, characterized by the presence of sinkholes, sinking streams, caves, large springs and highly productive water wells.

Karst aquifers are considered “triple permeability” aquifers — rain passes into them very quickly, Gonzalez explained. Any amount of rain is usually enough to keep the area out of the next stage, she said. It would have to be a drought of unseen proportions to affect the Edwards Aquifer, she added.

When the region is in a drought, the concern is not that the aquifer is drying up, Ruiz said — it’s that low water levels are a threat to local spring flows, including Comal Springs in New Braunfels and the San Marcos Springs in San Marcos. These springs are inhabited by threatened and endangered species, and water not flowing can negatively impact them, he explained.

Focusing on the entire ecosystem is “the holistic approach to managing the aquifer through a drought,” Ruiz said.

More, longer, drier

Due to climate change, Texas will likely see more, longer and drier droughts over the next century, Nielsen-Gammon said.

This won’t be due to a lack of rainfall — in fact, according to a report that Nielsen-Gammon and his team published in October, Texas will see record rainfall in the next few decades.

But the state will also see increased temperatures, which means water evaporating from the soil more quickly, and increased carbon dioxide levels, which will result in more plants popping up and using more water.

Despite these challenges, SAWS officials said they are prepared for droughts of all shapes and sizes — including for another drought of record. The 1950s drought resulted in widespread agricultural shortages, forcing many farmers to leave the state. Conditions were even drier than the 1930s Dust Bowl and resulted in many smaller water sources across Texas drying up.

Donovan Burton, vice president of water resources and governmental relations at SAWS, said the utility’s Water Management Plan takes into account future droughts equal to or worse than the seven-year drought of record. The 2017 plan, for example, considered the intensity of the 2011-2015 drought, Burton said. That drought was severe: between 2011 and 2015, San Antonio spent 48 out of 60 months in Stage 2 water restrictions.

The good news is that San Antonians are already pretty good stewards of water, said Karen Guz, SAWS’ director of water conservation. Thanks to years of public education, San Antonio is a low-water-use city, especially compared with other Texas metros, she said.

The utility is updating its water management plan, which it does every five years. That includes collecting public input, which is happening now.

A lot goes into updating the plan, Burton said. The utility works with third-party analysts who draw up forecasts and project water use for worst-case scenarios. The SAWS team also incorporates lessons learned from events such as Winter Storm Uri and simulations to develop an informed idea of what the plan needs to include, he said.

Planning for drought and water shortages is one reason SAWS has diversified its water sources over the past two decades, Burton added. That way, if something were to happen to one source, such as contamination, San Antonio would still have other sources to draw from.

While this is good news for the San Antonio area, other parts of Texas, especially rural areas, will still be deeply affected by these heavier droughts, according to Texas A&M Agrilife. Wells run dry. Cattle and crops are particularly sensitive to drought; cows graze less and hold off on reproducing, while plants struggle to survive. The dryness also can contribute to an increase in certain pests such as the cattle fever ticks, which can affect herds.

Where there’s smoke…

With more droughts will come more wildfires, Nielsen-Gammon said.

A correlation between drought and increased wildfire risk does exist, said Walter Flocke, regional wildland urban interface coordinator for the Texas A&M Forest Service, although it’s not as direct as people might think.

“Every time we see longer periods of drought, we see longer fire seasons,” Flocke said. “We may see some breaks in fire severity — drought doesn’t always mean 100 days without rain, right? It could be a couple of days with light rain — but in the long term, drought lengthens fire seasons and the grasses’ susceptibility to fire.”

Over the past two months, state officials have declared disasters in more than a dozen counties due to the rapid spread of wildfires across the state.

Rural wildfires are often dealt with by a county’s emergency coordinator or its emergency preparedness office. Large wildfires are one of the many scenarios the Bexar County Office of Emergency Management (OEM) has prepared for, said Bexar County spokesman Tom Peine.

“The OEM is in a process of constant training, readiness evaluation and iterative improvement of disaster response processes within Bexar County,” Peine stated in an email.

His confidence mirrors that of SAWS’ Burton.

“We absolutely prepared for [the next drought of record],” he said. “What we do, day in and day out, is we look at it from a 50-year perspective, a 10-year perspective, a day-to-day perspective, a month-to-month perspective — that is what we do. That’s what the community has charged us with doing.”

This story has been updated to correct Donovan Burton’s title.