- As city leaders consider expanding at-risk zone for wildfire damage, home builders say it could raise costs

- Is your neighborhood at high wildfire risk? | Here's how to check the city's wildfire risk map

- 'Be prepared now': Brad Panovich updates severe weather risk for Sunday

- 'Be prepared now': Brad Panovich updates severe weather risk for Sunday

- As anxiety around wildfires grows, Austin plans to add tens of thousands of acres to risk map

Pace of Harris County home buyouts slower than hoped for after Hurricane Harvey

From Houston Public Media:

On a hot day in July, a small audience of cars appeared camped out across the street from a demolition site. Local residents were there to bear witness to a highly anticipated event in South Kingwood: the last of the Forest Cove Townhomes were getting knocked down.

For the past five years, a complex of townhomes has sat empty and ramshackled after getting slammed with stormwater following Hurricane Harvey. According to one townhome owner, the complex saw up to 21 feet of water. Utility companies refused to turn the power back on, saying the damages were too severe, according to local officials.

The townhomes which sit on Lake Houston have flooded before. This led Harris County Flood Control District to select the complex for its voluntary buyout program funded by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. But the snail’s pace of these transactions, a veritable hallmark of most buyouts in Houston and nationwide, has carried a set of unintended consequences.

Vandalism, graffiti and trespassing have cropped up in the vacant structures, according to Joy Sadler, a resident who lives a few minutes away and heads the nearby property owners association.

“They look like a bomb went off,” Sadler said. “I mean they were flooded up to the second story, maybe the third. And they’ve been left like this with nothing done to them.”

In June, before the final demolitions, the townhomes were covered in crass graffiti. Shattered glass covered the ground. The garage doors were ripped off. Garbage was strewn everywhere.

Sadler said the vandalism has reached the community center and pool across the street. Local residents haven’t been able to use these facilities for much of the past few years.

In spite of the blight on the neighborhood, community grievances and safety concerns, the Forest Cove Townhomes is an example of a buyout success story by some measures. Houston Parks Board plans to convert the space into a trail for hiking and biking and connect it to the San Jacinto Bayou Greenway before the end of the year.

The end result: townhome residents are out of harm’s way and the park can hold water during future flooding events.

Unlike most buyouts, local government was able to purchase an entire cluster of homes. Experts say this is the most effective approach because the land can then be repurposed for public projects.

Houston Public Media Creative Services

However, homes are typically bought out in a patchwork fashion called checkerboarding. FEMA-funded buyouts require voluntary buy-in, which can be difficult to get across the board. New houses are prohibited from being built on buyout land, so these neighborhoods are often dotted with vacant lots that provide no commercial, residential or flood mitigation value.

Houston Public Media Creative Services

Even though long-standing challenges have plagued the program, experts agree that the number of buyouts needs to increase because of the growing flood risk in Houston caused by climate change and urban development.

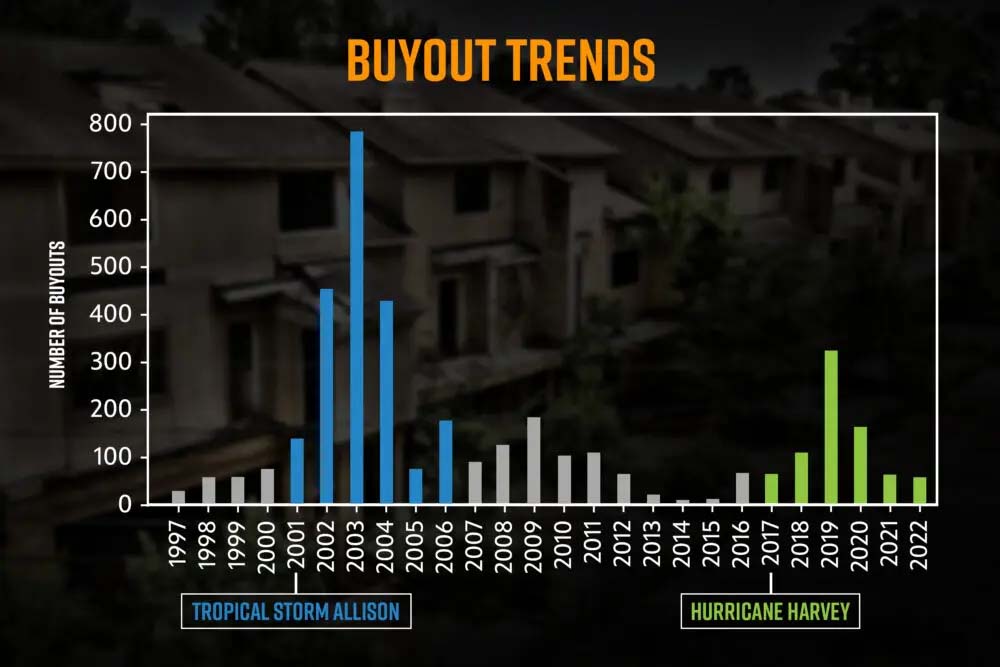

Records obtained by Houston Public Media, however, show that buyouts have been trending in the opposite direction. Harris County Flood Control District has closed on almost 750 buyouts since Hurricane Harvey, compared to 1,900 buyouts in the five years after Tropical Storm Allison.

Buyouts have more than halved, all while FEMA is investing more money than ever into buyouts. Harris County Flood Control District has been allocated almost $190 million since 2017, compared to nearly $50 million in the years after Allison.

“The decrease in numbers after Harvey has to do with the fact of all the buyouts that have been completed since Allison,” said James Wade, Property Acquisition Manager at Harris County Flood Control District. “There were less properties that were vulnerable (after Harvey) because they’d already been mitigated.”

Wade said this despite 5,000 properties still remaining on The District’s buyout list. These are homes in the floodplain that repeatedly flood and are considered prime candidates for the program.

The Flood Control District faces a big problem after almost every storm: failing to catch volunteers right after a disaster when they’re most motivated to take a buyout.

Federal funding only opens up after a presidentially declared disaster. The trickle down of those dollars from federal to state to local entities is often a long wait.

“It’s not so hard to get the volunteers, it’s hard to keep them engaged,” Wade said. “Where we lose volunteers is during that time it takes to secure the federal grant funds.”

HCFCD said it took 9 months to see the first tranche of federal funding after Hurricane Harvey.

“It’s hard to convince them, ‘hey, we’re submitting for federal grant dollars, we’re reasonably certain we’re going to get it, it’s going to take 8 to 18 months,” Wade said. “That’s a lot to ask an owner who had floodwater to their roof. Most people want to move on and get on with their lives.”

40 percent of volunteers dropped out after Hurricane Harvey, according to Wade. They chose to either repair or sell their homes on the private market — vulnerable again to flooding.

The buyout list is expected to grow in size, as the floodplain gets larger and FEMA updates its flood insurance maps.

“The buyouts are barely even a drop in the bucket of what needs to happen with respect to flood risks,” said Jim Elliott, a sociologist at Rice University who studies buyouts.

Houston Public Media Creative Services

He said buyouts are not keeping pace with development. The concrete from new construction exacerbates flooding by blocking the soil underneath from soaking up floodwater.

“(Buyouts are) not stopping people from moving into these neighborhoods,” Elliott said. “You think, ‘oh, a buyout? I don’t want to move there.’ But no, housing prices are rising in buyout neighborhoods.”

Elliott’s research focuses on who takes buyouts and the inequity that often shows up. He said people are hesitant to take buyouts because they don’t want to leave their communities. Kids don’t want to transfer to new schools. Families don’t want to lose touch with relatives and friends.

“The best case scenario is probably a managed retreat where people move a relatively short distance, get out of harm’s way and are able to stay sort of near their community and each other,” Elliott said.

His research found that residents from majority white communities were six times more likely to stay in the same neighborhood.

“In lower income communities of color, people didn’t have the same choices,” Elliott said. “So if they did take a buyout, they ended up a lot farther away from the house sold and from each other.”

Dolores Mendoza, a single mom with three kids, moved 15 miles away to the whiter and wealthier neighborhood of Kingwood after taking a buyout last year.

She was a 6th generation resident of Allen Field in Northeast Houston with dozens of family members living just a few blocks away.

“My mom, both my sisters, my grandma — everybody had a key,” Mendoza said. “If you don’t have a key, you know where the other spare key is. That’s how heavily we relied on everyone for everything. So that’s completely different now.”

Dolores Mendoza and her family celebrating Christmas in 2020. Because of the mandatory buyouts, this was the last time they celebrated in her childhood home.

Courtesy of Dolores Mendoza

Mendoza lived in Allen Field her whole life, besides from a short stint in Spring. But she was so homesick there, she decided to move back home.

“I moved back with the intention of it being my forever home,” Mendoza said. “When me and my (ex) husband bought it, we’re like ‘this is where our grandkids are gonna visit us.’ We had all these plans. So when we left, it was surreal.”

The family is now fanning out across the area. Her sister also moved to Kingwood, but other relatives are now a thirty minute drive away from Mendoza and her kids.

Over two years ago, she received a letter in the mail informing her that Allen Field was subject to mandatory buyouts, which is allowed through funding from the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The neighborhood is one of 62 areas that Harris County Flood Control District has identified for both voluntary and mandatory buyouts. Allen Field is six feet in the floodway and has repeatedly flooded. Mendoza remembers Tropical Storm Allison wrecking her mom’s house in 2001. She had to sleep on an air mattress for months.

During Harvey, she said the water rose so high, she couldn’t see the stop sign on the corner. A homeowner this time, Mendoza waited on her porch for a boat to rescue her, as the water crept up the stairs of her house elevated eight feet in the air.

Reflecting on these moments has helped Mendoza understand why buyouts are necessary, but it took a while for her to come around. A confusing and inaccessible process filled with legal jargon made it hard for her to see the forest through the trees.

“I didn’t understand what was going on,” Mendoza said. “I’m like, ‘what the hell?’ I’m writing down notes like, ‘okay, I’ve never heard of eminent domain, I need to Google that.’”

She eventually received what she considers a fair offer on her house and a relocation benefits package, which covers closing costs, moving costs and an added $19,000 bonus for staying within Harris County. Some homeowners might also be eligible for down payment assistance and closing costs on the new home.

In a competitive housing market, Mendoza said it was challenging to close on a new home.

Mendoza’s brother-in-law sat in knee-deep water while watching the news during Hurricane Harvey.

“I put in so many offers that were just turned away because (sellers) just didn’t want to deal with the county,” Mendoza said. “People are looking at three month closings, that’s insane to buy a house, especially in this market.”

She eventually moved into a house with a pool, a request made by her kids. At the end of the day, she was financially made whole by the buyout program.

However, Mendoza recognizes that she is a citizen who speaks fluent English. Not everybody in Allen Field, a majority Hispanic neighborhood, has that background. That put some residents at a major disadvantage, said Shirley Ronquillo, a community organizer with The Department of Transformation.

“The letters announcing the mandatory buyout were in English only,” Ronquillo said. “So you are releasing these into a community that speaks Spanish or has different literacy levels and this is so confusing.”

HCFCD representatives, however, said letters in Spanish were sent.

But that’s just the beginning of a long, intimidating process. Some residents are waiting years for offers that are too low. Others are struggling to find an affordable place to live.

Norma Escalona, one of many who complained at a Commissioners Court meeting in August, said she has been waiting months for her check to arrive.

“Up until this point, I haven’t received any payment for my home,” Escalona said through a translator. “We’re right at our limit financially and it’s taking a lot for us to try to get ahead of all these expenses. It’s not fair for us to have to go through this because of the program.”

Undocumented immigrants face an even bigger hurdle. Federal rules block them from receiving relocation benefits, even though they’re forced to take the buyout like the rest of Allen Field. These benefits can add up to tens of thousands of dollars or more, and play a big role in making people whole in the process.

Ronquillo said there were many who were afraid to engage at all.

“At that time, because our political situation was different, we had a different person in the presidential office, (the reaction) was fear,” Ronquillo said. “Because at that moment, there was fear of public charge.”

Harris County makes it clear on their website: accepting these benefits will not affect your immigration case. After months of community organizing, the County launched the SAFE Fund last year, a $2.3 million pot of money that would assist with relocation benefits for people without papers.

Improvements have been made, but there are still a lot of challenges, Ronquillo said. The biggest complaint is that each step of the process seems to drag on.

Mendoza’s mother, Irene Torres, is still waiting on the county’s offer on her house — more than two years after the mandatory buyouts in Allen Field were first announced.

She hasn’t been able to fix her home after the pipes burst during the winter freeze in 2021.

Irene Torres is part of the mandatory buyouts in Allen Field. She is still living with damages from the 2021 winter freeze.

“These old houses, you gotta keep them up, but because of the buyout, we can’t,” Torres said. “They told me don’t fix, so I’m not going to waste my money, but everything is just falling apart.”

She and her 16-year-old son are living with cracks in the floor, roaches and rats. Her son, who has asthma, steers clear of what once was his home gym because mold is growing on the walls Torres pointed out the carpet squares she laid down in the kitchen covering holes in the floor.

If these buyouts weren’t mandatory, it’s often at this point when homeowners give up.

James Wade said mandatory buyouts might become a tool the Flood Control District uses more often in the future.

“Potentially, yeah,” Wade said. “Again, it’s controversial. No one wants to force someone to move from their home if they don’t want to. But the flip side of that is at what point is government being negligent? Are we allowing people to live in harm’s way? Is that acceptable?”

Kayode Atoba studies buyouts at Texas A&M’s Institute of Disaster Resilience in Galveston. He says the county needs to increase the number of buyouts if it’s serious about reducing flood risk to properties deep in the floodplain.

“The flood risk for those places would not get better, it’s actually going to get worse because development continues to occur,” Atoba said.

A paper he recently wrote stresses taking a proactive approach, such as open space protection — the idea of not just buying out houses, but buying property before houses even get built in certain areas.

“It’s backwards,” said Sam Brody, who co-authored the paper. “Other countries and cultures look at the United States with miffed expressions because of the way we continue to flood, respond, rinse, repeat, over and over again.”

Brody said the structure of the FEMA programs, which makes up three quarters of Harris County buyouts, is inherently reactionary.

“My biggest concern is that despite our best efforts, the cost of flooding, the impact to communities is spiraling upward,” Brody said in his testimony to a U.S. Senate Committee in June. “By all accounts, the problem is getting worse and it’s a national priority to reduce our losses.”

At the very least, James Wade with the Flood Control District says having local dollars ready to buy people out right after a flood could help, but it’s really federal funding that makes the biggest impact.

“If we had a pot of money available, immediately following a disaster, I think we’d be a lot more successful,” Wade said.

Congresswoman Lizzie Fletcher has filed a bill that could make that possible. Instead of waiting months for FEMA funding like after Harvey, Harris County could move forward with buyouts immediately and asked for reimbursements later.

Houston Parks Board said construction of the greenway will take 60-90 days. The park will have trails for local residents to hike and bike on.

Houston Parks Board

The bill has passed the House, but hasn’t yet been brought for a vote in the Senate.

“We’re continuing to apply the lessons that we’ve learned from Harvey,” Fletcher said. “What were the impediments to our recovery after Harvey? What are places where we can help address some of the challenges?”

Joy Sadler and her neighbor Matt Tielkemeijer think five years was way too long to complete the buyouts in Forest Cove. But now that the townhomes are demolished, they feel their community has the ability to really move on from Hurricane Harvey.

Tilkemeijer said there is a lot of hope for this area in the years to come.

“Once this is gone and they reform this land and finish the greenway, this will be a beautiful area again,” said Tielkemeijer.

Click here to down the full dataset of buyouts by Harris County Flood Control District.