Irregularities in COVID Reporting Contract Award Process Raises New Questions

An NPR investigation has found irregularities in the process by which the Trump administration awarded a multi-million dollar contract to a Pittsburgh company to collect key data about Covid-19 from the country’s hospitals.

The contract is at the center of a controversy over the Administration’s decision to move that data reporting function from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — which has tracked infection information for a range of illnesses for years — to the Department of Health and Human Services.

TeleTracking Technologies, the company that won the contract, has traditionally focused on creating software for hospitals to track patient status. And there are questions about how it came to be responsible for gathering data in the midst of a pandemic.

Among the findings of the NPR investigation:

- The Department of Health and Human Services initially characterized the contract with TeleTracking as a no-bid contract. When asked about that, HHS said there was a “coding error” and that the contract was actually competitively bid.

- The process by which HHS awarded the contract is normally used for innovative scientific research, not the building of government databases.

- HHS had directly phoned the company about the contract, according to a company spokesperson.

- TeleTracking CEO Michael Zamagias had links to the New York real estate world — and in particular, a firm that financed billions of dollars in projects with the Trump Organization.

An abrupt change during the pandemic

When the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees the CDC, sent out a directive to the nation’s hospitals in April announcing it would be using TeleTracking as an option to collect COVID data, Carrie Kroll didn’t give it a second thought.

It just seemed like one more form hospitals might need to fill out.

Kroll is with the Texas Hospital Association, and balked only after the HHS suddenly announced in July that hospitals could no longer report COVID data through the CDC, but would instead be required to do so through the HHS-TeleTracking system or their state health departments.

This is the sort of data that has been closely watched since the outbreak of the pandemic: from beds, to personal protective equipment (PPE), to detailed demographic information on suspected and confirmed COVID patients.

“Up until the switch, we were reporting about 70 elements and we’re now at 129,” Kroll said, scrolling through a five-page list of the information now required. “I mean, clearly we’re in the middle of a pandemic, right? I mean this isn’t the type of stuff you try to do in the middle of a pandemic.”

Hospitals were only given days to start sending all this information to TeleTracking. The HHS explained the sudden change by claiming the new database would streamline information gathering and help in the allocation of therapeutic pharmaceuticals like remdesivir.

But thousands of hospitals had used the CDC system for years to report infection control data. So it raised questions: Why the change? Why now?

The CDC has been tracking these numbers for some 15 years. And while its system isn’t perfect — it requires all the information to be entered manually, for example — it is unclear why the government, already underwater with the spread of COVID, didn’t decide instead to tinker with the existing system.

Robert R. Redfield, the CDC’s director, said the reason HHS chose TeleTracking was because it provided “rapid ways to update the type of data that we’re collecting” and that it “reduces the reporting burden,” none of which, given the duplication of Kroll’s experience around the country, seems to be happening.

The TeleTracking software, for example, requires all the data to be keyed in manually, just like the CDC once did.

An HHS spokesperson said that the COVID response required that they move quickly to implement a new system, “even when more time might be desired. We acknowledge that hospitals were not given significant lead time to prepare for these changes.”

TeleTracking’s ties to Trump Organization financiers

The CEO of the company, Michael Zamagias, came from the real estate sector. He founded Zamagias Properties, a real estate investment and development company, in Pittsburgh, PA in 1987.

The company went on to develop iconic office buildings, shopping centers, and malls in Pittsburgh and Virginia, and its success helped Zamagias become a fixture outside Pittsburgh and, in particular, in the New York real estate scene.

Zamagias is a longtime Republican donor and community philanthropist, giving generously to Pittsburgh schools and youth programs.

One of the young people who came to Zamagias for advice and counsel was a New Yorker named Neal Cooper, though he was hardly new to business or real estate. Zamagias became the young Cooper’s mentor. He gave Cooper an internship.

Neal’s father, Howard, was the named partner in a Manhattan company called Cooper-Horowitz, one of the largest privately-held real estate debt and equity firms in the country.

“Cooper did business with Michael in the late 1980s,” Neal Cooper told NPR, referring to his dad’s company. “I don’t know if we ever did big deals with him, but we ran in the same circles. I learned a lot from Michael. He was always one or two steps ahead of the next guy.”

Cooper-Horowitz handles debt and equity in all classes of real estate and specializes in the hospitality industry.

And in that vein, it did billions of dollars of work with the Trump Organization on projects like the Trump International Hotel & Tower in Chicago.

“I didn’t handle Trump’s account, but I’ve been in meetings with Trump,” Cooper said. “We did tons of business with him, billions of dollars of business.”

And there are other suggestions of a close relationship between Cooper-Horowitz and the Trumps.

Ivanka Trump has attended a rather famous holiday party the company holds in New York every year. The firm has given to the Trump Foundation. And Richard Horowitz, one of the company’s principals, is credited with helping connect the Trump Organization with Deutsche Bank, the German bank that has financed over $2 billion in Trump projects over the past two decades.

There’s no evidence that these professional relationships are why Zamagias and TeleTracking received the multi-million dollar contract. Through a spokesperson Zamagias said that he hadn’t talked to anyone at Cooper-Horowitz in years, and all his company’s contact with the administration came through HHS.

But Congressional investigators are now eager to find out if that relationship somehow played a role.

The White House did not respond to questions about whether it was involved in the awarding of the TeleTracking contract, or whether White House staff had any relationship with Zamagias.

An unusual contracting process leads to multi-million dollar TeleTracking deal

Initially, there was confusion about the way HHS awarded the contract to TeleTracking. Public records originally displayed it as a sole-source contract — essentially a no-bid deal.

But after a Senate inquiry and controversy over the mandatory shift to the TeleTracking system, HHS said that there had been a “coding error” and that it had in fact been awarded after a competitive process.

“The TeleTracking contract was part of a competitive solicitation process and was not sole source,” an HHS spokesperson said. “One of the websites that tracks federal spending contained an error that incorrectly categorized the award as sole source. That coding error is being corrected.”

That competitive process, HHS said, is known as a Broad Agency Announcement.

BAAs are essentially call-outs to private industry to provide innovative solutions to general problems in which a simple straightforward solution may not be available — it isn’t meant for something like a government database that replaces an existing CDC function.

A standard government contract would usually lay out a series of specific requirements or specifications. Not so with BAAs. By their very nature, they are less competitive than other types of government contracting processes because they may generate an array of solutions that may not necessarily be comparable.

In a statement, an HHS spokesperson said that the BAA is a “common mechanism… for areas of research interest,” and asserted that the healthcare system capacity tracking system previously used by the CDC was “fraught with challenges.”

HHS has said that six companies bid for the contract but declines to say who they were or release the evaluations that the department would have done before awarding the contract to TeleTracking.

“Federal acquisition regulations and statutes prohibit us from providing information about other submissions,” an HHS spokesperson said. The spokesperson added that the BAA was released in August 2019, and that the agency promoted it on social media, in newsletters, and in emails.

But NPR reached out to more than 20 of TeleTracking’s competitors in the fields of hospital workflow management and infection control data and was unable to find a single company that said it had bid on this contract.

One major company told NPR that it hadn’t even heard about the HHS announcement.

There is another wrinkle here. A spokesperson for Zamagias told NPR that HHS reached out to the company directly — by phone — because it knew the company from its hurricane and disaster preparedness work.

It is unclear when that phone call was made.

Congressional investigators probe HHS and TeleTracking

The whole process by which TeleTracking got the contract strikes Virginia Canter, Chief Ethics Counsel at Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, as out of the ordinary.

It isn’t just the use of the BAA. It is that HHS “now requires 6,000 hospitals to enter this data” in what looks like proprietary software, which the federal government may need to pay for in the future, Canter said the current contract ends in September. The Zamagias spokesperson told NPR that TeleTracking hopes for a contract extension — and that potentially means millions of dollars more in the future.

“We do anticipate needing to continue this contract,” an HHS spokesperson said.

Congress is also looking into irregularities in the contract process and the decision to shift the data gathering from CDC to HHS. Sen. Patty Murray, a prominent Democrat on health care, first raised questions about the HHS contract in early June.

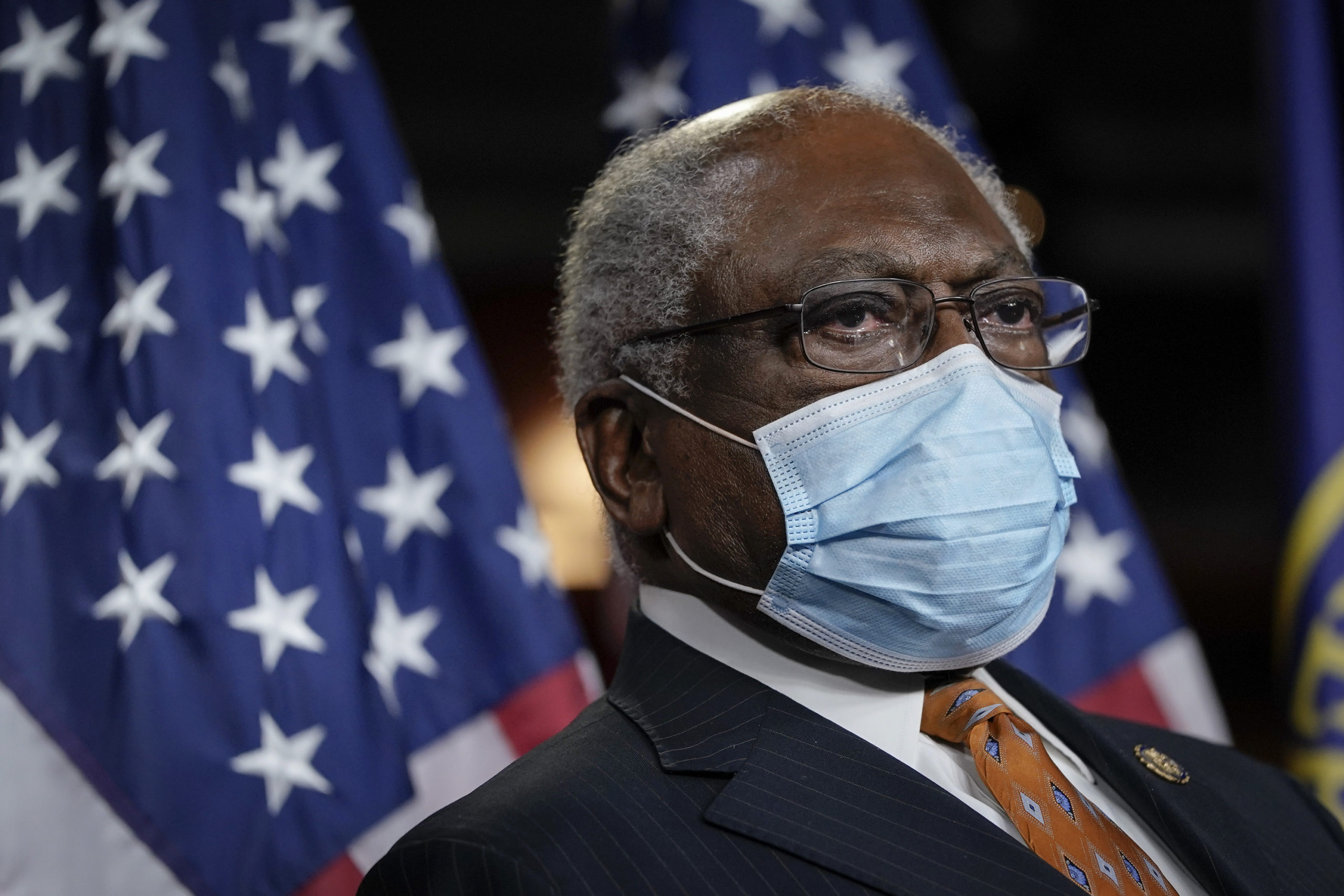

And Rep. James Clyburn, who chairs a Congressional subcommittee overseeing the coronavirus crisis, and House Oversight Committee Chairwoman Carolyn Maloney are both demanding answers about what happened.

While the inquiries were originally focused on HHS, Clyburn sent a letter to Zamagias Tuesday asking for information on the contracts, emails and communication exchanged with HHS in a bid to understand how TeleTracking came to land the $10.2 million six-month contract in the middle of a pandemic.

“Your company has previously been awarded a handful of small contracts with the Department of Veteran’s Affairs, but your contract with HHS is nearly twenty times larger than all of your previous federal contracts combined,” Clyburn wrote in his letter to Zamagias.

9(MDAzNTg0OTAyMDEyOTc4NzIxNTYxN2U1Yg004))