- Helene forced a North Carolina restaurant owner to leave his home. He just lost his 'Cabin of Hope' in recent wildfires

- Carolina wildfires grow, evacuation orders still in effect

- Helene forced a North Carolina restaurant owner to leave his home. He just lost his 'Cabin of Hope' in recent wildfires

- Severe weather likely in the Carolinas on Monday

- 3 dead, flash floods overwhelm South Texas, with some areas receiving more than 12 inches of rain

#TBT: Marker at Rose Hill Cemetery memorializes unidentified victims of 1919 hurricane

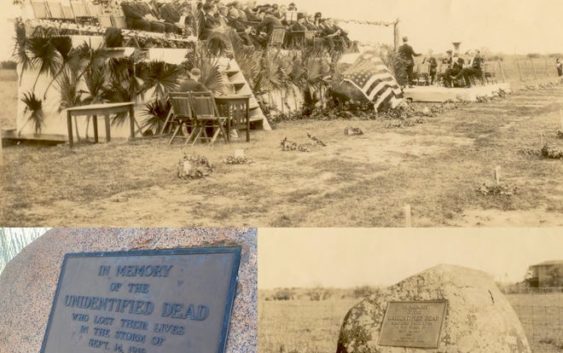

One hundred years ago, 3,500 people gathered in Rose Hill Cemetery to honor the unidentified victims of the horrific hurricane of 1919.

The storm of 1919 was a devastating event in the city’s history. On Sept. 14, a hurricane made landfall 25 miles south of downtown Corpus Christi, bringing with it 115 mph winds and a 16-foot storm surge that inundated downtown and North Beach. People were swept into the water as their homes and businesses collapsed in the churning surf. Many drowned in the chaos, and both living and dead were swept across Nueces Bay on storm debris and deposited on White Point in Portland.

As bodies were recovered, authorities attempted to identify the victims quickly in the South Texas heat. The Nueces County Courthouse and West Portland School became makeshift morgues as families, friends and neighbors attempted to identify the dead. Many victims were coated in oil from ruptured storage tanks on Harbor Island, or battered beyond recognition by huge cotton bales from the wharf in Corpus Christi and destroyed buildings from Port Aransas.

More:Corpus Christi’s 1919 hurricane brought destruction, but reshaped the city for the future

The official death toll was 284, but researchers speculate the count may have been anywhere between 600 to 1,000 victims. Many of the unidentified were interred in mass graves near Portland, around 41 sites spread around the area, with as many as 50 victims placed inside. The streets outside the Nueces County Courthouse were lined with carpenters building makeshift coffins.

A month and a half after the storm, Corpus Christi funeral director Maxwell P. Dunne began the process of exhuming the bodies at White Point for reburial. They were loaded onto a barge and moved to Corpus Christi, where workers attempted to identify victims.

Workers had taken notes on each victim, which were later transcribed onto index cards, in hopes someone searching for a family member or friend would recognize them. In 1999, Dunne’s grandson Max Dunne described the identification lists in the funeral home’s possession.

“It had to be grim work for someone to do,” Dunne said. “They wrote down this information never knowing if anyone would come back.”

Some cards gave detailed descriptions of teeth condition and filings, jewelry and victim’s clothes. Others were terse.

“White male, about six years old, badly decomposed, no marks of identification.”

“Supposed to be white female, no clothing, badly decomposed and nothing left for identification. November 4, 1919.”

Following the attempts at identification, the victims were reinterred at Rose Hill Cemetery in another mass grave, with plans for a marker to be added later.

More:#TBT: Survivor of Corpus Christi’s 1919 hurricane created Saffir-Simpson scale

On Jan. 25, 1923, the local chapter of the Red Cross unveiled a memorial at Rose Hill. Several days prior, a proclamation from Mayor P.G. Lovenskiold ran in the Corpus Christi Times, declaring Jan. 25, 1923, as a memorial day to the victims of the 1919 storm, but especially the unidentified who had been laid to rest at Rose Hill four years earlier. He asked that businesses close to allow all citizens to attend the event.

At the memorial service in 1923, the American Red Cross’ head of the disaster division, Henry M. Baker, presented the monument — an 8-ton chunk of granite with a bronze marker — to the city and mayor. A 50-person choir, made up of choir members from area churches, sang at the program accompanied by the Elks band, along with speakers from area churches and the mayor.

On Wednesday, the Nueces County Historical Commission hosted a 100th anniversary commemoration of the original dedication. Members of the commission spoke of the original dedication and displayed images and a program from that event next to the monument, located along the fence on the east side of Rose Hill Memorial Park.

Historical commission Chair Kathy Wemer thanked the handful of hardy souls who came out in the cold wind to remember the victims. Debbie Zuniga with the historical commission presented research on the storm, marker and 1923 memorial service. The boulder was mined from Llano County and, with the exception of the area where the bronze marker is attached, was left untouched by tools.

“May this 8-ton memorial boulder be a continuous reminder of the strength and courage of the ordeal these victims faced,” Zuniga said during the Wednesday memorial.

“May they rest in the peaceful arms of our Lord and may they never be forgotten.”

Allison Ehrlich writes about things to do in South Texas and has a weekly Throwback Thursday column on local history.